Industrial heritage

Nick Thomas-Symonds, the MP for Torfaen in South Wales and chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Industrial Heritage, has every reason to be passionate. His own family worked in the South Wales coalfield, and his constituency is the home of the Big Pit at Blaenavon which is part of the World Heritage Site. On 11 July 2019, a summit of the APPG met at the V and A.

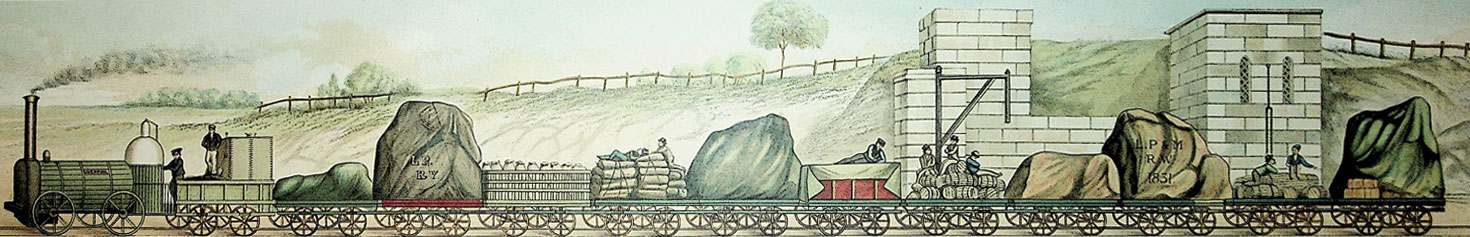

The director of the V and A, Tristram Hunt, pointed out that the museum brings together two strands. The first is the collection of the East India Company; the second is the celebration of industry at the Great Exhibition of 1851. The V and A is the embodiment of Industry and Empire, the title of Eric Hobsbawm’s classic economic history of modern Britain. Whether the V and A adequately interprets its imperial background is a moot point. It is trying to make links with industry in conjunction with regional museums in five industrial centres to inspire thinking about design – and the new base in Stratford in east London will rescue the industrial heritage of the Lea valley and London as a major centre of the industrial revolution.

Much effort is now being placed on the legacies of slavery in the country house. We should also think about the connection with industry – whether it be the investment of compensation received by slave owners that was reinvested in railways and factories, or the cotton that was spun and woven in the mills of northern England. This link was not made during the summit, which instead focussed on how the mills of northern towns might be reused – the subject of excellent presentations by Historic England and the developer, Capital and Centric. The mills can make stunning houses and offices, but less attention was given to presenting a working mill or how to interpret the wider economy of a mill town and region. The National Trust mill at Styal provides insight into an early factory and its apprentices – but preserving a large steam-powered mill from the later nineteenth century is more of a challenge. The surviving working Queen Street Mill in Burnley has faced closure. And how to show the flow of cotton from the United States through Liverpool and Manchester, to explain the differences between spinning and weaving towns with their distinctive patterns of employment of men, women and adolescents, and then the export of yarn and cloth to India and the impact on the Raj?

Around the country, there are about 600 publicly accessible industrial sites, mainly run by volunteers, with some advice from an Industrial Heritage Support Officer funded by Historic England. These sites are small and run on a shoe string. The preservation and interpretation of coal mines and steel works are a different order of magnitude. Coal was fundamental to the industrial revolution and to the beginnings of global warming; it fuelled the iron works and railways; allowed London to become the world’s greatest city; and was exported around the world for the steam ships and railways of the first great age of globalisation. Only Big Pit remains open as an underground museum; Chatterley Whitfield in the Potteries is closed. Very few winding gears survive as visual reminders of a once mighty industry – and the industrial heritage is not only the pit itself – it is also housing, miners’ libraries, clubs and institutes, the ‘miners’ parliament’ in Durham, and the docks and staithes on the Tyne and Wear. Steel works and engineering workshops are even more difficult to preserve. Is the answer to treat them as monuments in the landscape, which has happened in the Ruhr where winding gear has been preserved or in Luxembourg where blast furnaces have been incorporated into a university campus?

The discussion raised questions about the regeneration of decaying industrial towns and the interpretation of ‘heritage. Industrial museums have traditionally been more concerned – as one contributor put it – with cogs rather than clogs, and we need to think about the social history of the mills and mines as well as the machinery and technology. After all, one of the main incentives behind mechanisation in the industrial revolution was to replace expensive men with cheaper children and women. We also need to think more about the link between industry and empire – something that has been done at Richard Arkwright’s Cromford mills which is now a world heritage site. And the largest industrial plants of the industrial revolution were state-owned and operated naval dockyards. They were vital for the growth of the British empire and trade, and had deep links with domestic industries such as copper for ships’ bottoms and iron for cannons and anchors. The story of the navy is told at the National Maritime Museum and Chatham naval dockyards. The summi focussed on how to reuse the buildings of Britain’s industrial prime and to regenerate former industrial towns. A second summit might ask how we can think about Britain as the world’s first industrial nation.