Brexit: a deep history

A shallow history of Brexit could start with the referendum in June 2016 when 33,577,342 electors voted, with 51.9 per cent opting to leave and 48.1 per cent to remain on a turnout of 72.2 per cent. It only needed 635,000 of those voting to change their mind for a different result which was what was widely expected even by Nigel Farage. Much of the subsequent debate turned on short-term contingent factors concerning the campaign – the articulation of the message ‘Take Back Control’, the focus on getting out people who never voted, the exploitation of the refugee crisis, and the use of data from Cambridge Analytica and Facebook. These issues are all Important, and if the vote had gone slightly the other way, we could not be where we are in 2019.

But focussing on the narrow victory for leave misses two wider points:

- Before the 1975 referendum, British engagement with European integration was distinctive and always differed from the founding members, never fully committed. Why?

- There was considerable change since the 1975 referendum when 67.2 per cent were for remain and 32.8 per cent to leave, on a lower turnout of 64.5 per cent. The only two areas with a leave majority were the Western Isles and Shetland. Why this shift since 1975?

These two questions shape a longer or deeper history of the second referendum.

WHY NOT ENGAGE IN THE INITIAL CREATION OF THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC COMMUNITY?

Britain’s circumstances after the war were distinctive and unlike the rest of western Europe, so that there was rationality in the guarded response to such initiatives as the European Payments Union and the Coal and Steel Community. In particular, there were four features.

- Responding to post-war reconstruction

In continental Europe, the experience at the end of the war offered reasons for integration:

- The experience of defeat and occupation led to a desire to create a stronger bloc to prevent being overwhelmed by the Soviets and United States

- There was a strong sense that the traditional nation state had failed the people: the recreation of trade for prosperity and welfare for stability rather than a race to the bottom needed supranational bodies to work with nation states.

Britain was not defeated or occupied; rather, the war validated the legitimacy of the state. There was less concern with being overwhelmed by the United States, and no reason – as in France or Italy – to fear powerful domestic Communist parties.

Britain did have serious economic issues that needed to be resolved to which the answer was not European integration

- Debt to US: the end of Lend Lease and the

terms of the post-war loan had conditions attached to end imperial preference

and restore convertibility of the pound

- Sterling balances in India, Egypt and elsewhere had to be paid down

By definition, the defeated or occupied powers did not owe money to the US and had no accumulated large holdings of foreign currency overseas – the economic problems at the end of the war were radically different.

The British government therefore had different problems, and response to European integration was rational, at least in the short-term.

Alan Milward rejects the idea that decisions by the British government after the war were blinkered, atavistic or pathological. Rather, they arose from rational thinking about how to adjust to the post-war world. They did not succeed which is not to say they were foolish. British government’s thinking was shaped by two issues: the sterling area and imperial preference..

2. Sterling area

Britain emerged from the war with huge debts to empire in sterling payments for food, raw material, and military payments. As a result, sterling formed about 80 per cent of world reserves, more than before the war: there was a paradox that the war weakened the British economy but increased sterling’s importance in global reserves.

These sterling balances were not convertible into other currencies and were ‘blocked’. There was a major issue of how to deal with them:

- Write them off/down, treat like Lend Lease received from the United States– some wanted to do this, but it was seen as unwise given the prospects of independence for India, and the immorality of taking away accumulated sterling after India suffered so badly from the famine in the war.

- Turn the balances into funded debt and pay interest – but why would holders agree to take a income stream when they wanted to spend the money on development?

- Go for a long, slow grind of paying down

The problem of sterling balances meant the British government could not engage in the same way as Europeans in the European Payments Union which was designed to stimulate intra-European trade which was vital to Europe but less so to Britain given that European markets were smaller and sterling balances were the major issue.

And there were differences over the form of European integration – Britain did not welcome a customs unions with supranational institutions [Saunders 34]

This relates to the other key postwar issue: what to do with imperial preference

3. Imperial preference

Imperial preference was adopted in 1932 in response to the great depression; it formed part of a wider move to trade blocs throughout the world. In 1930-33, the proportion of imports from empire rose from 27 to 38 per cent. [O’Rourke]

In 1951, Australia alone took 12 per cent of British exports – more than the Six founding members of the EEC.

1952-54 Commonwealth took 48 per cent of exports – Six 19.6 per cent. [Saunders 41]

There is a link with different policies for agriculture: Britain had a very low proportion in agriculture from mid-19th century [1871 22.6 per cent when just over 50 per cent in France], and opted for free trade in food, sold at world price. In the 1930s, the British government retained this approach through deficiency subsidies to cover the gap between costs for British farmers and world prices, which were paid by general taxpayers. In Europe, prices were kept above world prices by protectionism – hence, support for farmers fell on consumers. The politics of food and agriculture radically different

To look beyond Europe was not insular but a sober though short-sighted appraisal [Saunders 41]

The Six traded mainly with themselves so the EPU made sense to kick start trade – Britain traded mostly outside Europe, so why disrupt trade for doubtful benefits?

The Americans wanted Britain to abandon imperial preference in return for Lend Lease and a post-war loan – but the British government realised this was not practical.

There was a debate in 1946 over a European Customs Union: the idea was proposed by Ernie Bevin, foreign secretary, but opposed by a Cabinet committee led by ministers concerned with the economy – Hugh Dalton and Stafford Cripps. The report in 1947 found that a European Customs Union would not be the best possible outcome for Britain – but if one were formed, Britain should join, for exclusion would be harmful.

Cabinet agreed to consider an empire customs union; a combined empire and commonwealth customs union; a European customs union; and the relationship between the empire and a European customs union. Meetings to discuss European Customs Union foundered on how to reconcile with imperial preference [Grob-Fitzgerald 68-9, 75]

A free trade area was more reconcilable with imperial preference than a customs union: in a free trade area, it would be possible to have one’s own trade policy (as in NAFTA) and border checks. In a customs union with a common external tariff, border checks were not needed – but it follows that all goods coming in from outside had to pay the same tariff, and UK could not offer lower tariffs to say New Zealand lamb than did France.

Also linked with views on form of cooperation

4. Intergovernmentalism versus supranational institutions

The idea of Commonwealth did not assume supranational institutions, and Britain obvious had the leading role. The British government would not easily accept a supranational Europeanism in which it was not the dominant player. The European Coal and Steel Community – the precursor of the EEC – had a supranational high authority and court of justice

British preferred the Organisation of European Economic Cooperation which was an intergovernmental body to divide up Marshall Aid, exchange information and discuss issues.

Britain did not need to rebuild institutions after war, did not face issues of collaboration/resistance – instead, victory in the war enhanced the legitimacy of institutions in a myth of standing alone against tyranny. Saunders 40 points out that Britain was with and not of Europe: issues were discussed with Europe but without an intention of joining in the process of supranationalism. This was found on left and right:

On the left, there was concern that supranationalism wold limit democratic socialism: why nationalise the commanding heights of coal and steel only to hand them to a European body? Herbert Morrison commented : ‘It’s no good – the Durham miners won’t wear it’. [Saunders 42]

On the right, there was a sense of global power. Anthony Eden remarked that ‘Our thoughts move across the seas to the many communities in which our people play their part, in every corner of the world. These are our family ties. That is our life’.

This view was not confined to the right: Harold Wilson said in 1965 our frontiers are in the Himalayas and that he would prefer to withdraw half the troops from Germany than any from Far East.

The British government withdrew from the Spaak talks in 1955 and devised Plan G of 1956 for an industrial free trade area under the OEEC. This could maintain imperial preference and was intergovernmental. Britain withdrew from European discussions and the treaty of Rome which had a customs union. Instead, it set up EFTA in 1960.

Hence thinking about customs union which is now a key issue in the debate over Brexit goes back to the immediate post-war period – it was just not seen as significant as it was for European economies

But by the 1960s, attitudes were changing which takes me to a second question:

WHY DID ATTITUDES CHANGE SO THAT BRITIAIN JOINED THE EEC WHICH WAS REAFFIRMED IN 1975 REFERENDUM?

In 1971, 244 MPs voted against joining, 356 for. Only 39 Conservatives voted against the government and against membership – about 80 per cent voted for; 69 Labour MPs voted for membership, against the party line ie about 70 per cent were against.

Pro-European Conservatives wanted the Commonwealth model but now they had no choice except to enter a body with a supranational structure; and one with CAP locked in. Why did they accept the change? There were four main reasons.

- A wake-up call

The dangers of relying on the sterling area and imperial preference were clear: they were soft markets, and British firms were not competing with better quality goods from Germany or more advanced consumer goods.

By 1962, Britain traded more with the Six than with the Commonwealth. Now, it was not a gamble to join but an acceptance of reality. Membership of the EEC was part of a Conservative strategy for competition at home and abroad.

A common trope in the 1960s was that Britain was the sick man of Europe, suffering from the British disease of inflation, low productivity, industrial unrest which reached its nadir in the three-day week.

The response of the left response: in December 1974, Tony Benn thought that the final collapse of capitalism might only be weeks away – why prop it up with Tory measures like the EEC? He wanted socialist planning whereas Conservatives favoured expanded market capitalism.

On the right, there was a need to break out of cycle of decline: membership of the EEC would be a wake-up call of competition in faster growing economies. Edward Heath in 1971 remarked that ‘For 25 years we’ve been looking for something to get us going again. Now here it is’. He wanted Britain to be more than ‘to nestle on the shoulders of an American President’. Membership of the EEC would be dynamic and bracing, which Fintan O’Toole likens to the cold showers and beatings of English public schools.

The Director in April 1975 captured the mood: ‘The economic problems facing Britain are so numerous and so urgent that Gladstone, Keynes, Adam Smith and St Francis rolled into one would find it hard to affect them’ [Saunders 155]

Thatcher campaigned for membership – it meant a single market would would break restraints on trade.

Sovereignty was discussed but as second order issue:

Vic Feather, union leader: Britain cannot go it alone – would be knackered; sovereignty was not important. ‘The price of oil is not determined by the British Parliament. It is determined by some lads riding camels who don’t even know how to spell national sovereignty’. [Saunders 179-180]

Alec Douglas Home 1975 [Saunders 245]:

I do not see much point in parading a banner called sovereignty, if at the same time trade, strength, authority and security slid away. We had full sovereignty in 1914 and in 1939, but it did not stop war, and victory only came when we shared with others in an alliance. We had sovereignty in 1931 but it did not prevent three million unemployed.

O’Toole 11: ‘A common theme in the early 1970s is that Britain is such a failure that it has no choice but to join the Europeans. The image is not that of a fabulous dynastic union but, rather, of a grumpy old bachelor settling for a bad marriage because the alternative is a slow death in miserable loneliness’.

2. End of delusion of imperialism and great power status

Despite Wilson’s claims that Britain was a great power, in 1967 Britain withdraw from east of Suez.

1971 White Paper: in a generation Britain would have renounced the imperial past and a European future, leading to uncertainty about its place in the world. There was a feeling of dejected resignation [O’Toole 12] Membership was primarily sold as a remedy for economic ills – not a strong emotional connection, but pragmatic and instrumental.

1975 remainers argued that unrestrained nationalism led to war and Britain needed to join Europe to stop war. The posters for ‘Britain in Europe’ used the poppy as their symbol and the dove of peace. One poster proclaimed ‘On VE Day we celebrated the beginnings of peace. Vote YES to make sure we keep it’; another commented that ‘Forty million people died in two European wars this century. Better lose a little sovereignty than a son or daughter’. Ted Heath – a lieutenant colonel in the war – said that he was ‘entirely prepared to make a contribution of national sovereignty to the building of peace in Europe’. The 26-part documentary on The World At War was shown in 1973-74 – the public was receptive to the idea that European cooperation was an alternative to the clash of competing sovereignties [Kidd LRB 25 Oct 2018]

3. EEC was an alternative to socialism – or was it a capitalist bloc?

In 1970s, Conservatives were the European party: the EEC offered competition, a growing market and was not socialist which offered a threat at home, for example with Benn’s Alternative Economic Strategy.

Labour was more hostile to the EEC as a capitalist bloc. Labour argued that the EEC was less multiracial and harmed the undeveloped world with its protectionist policies. EP Thompson defined the EEC as a group of fat, rich nations feeding each other goodies’ and united by ‘introversial white bourgeois nationalism’ [Saunders 18]. The EEC seemed to run counter to the radical ideas of the New International Economic Order for justice between developed and undeveloped countries.

The Labour National Executive Committee in 1962 made the point that ‘Unlike the Six, Britain is the centre and founder member of a much larger and still more important group, the Commonwealth. As such we have access to the largest single trading area in the world; and political influence within a world-wide, multi-racial association of 700 million people.’ The real dangers for the future were not Germany v France, but Communists against non-Communists and the inequalities of developed and underdeveloped, white and coloured races. More than any advanced country, Britain had the chance to resolve these issues – the Commonwealth was ‘a truly international society, cutting across the deep and dangerous divisions of the modern world’. ‘If we are ever to win peace and prosperity for mankind, then the world community that must emerge will be comprised of precisely such diverse elements as exist in the Commonwealth today’. [Grob-Fitzgerald 292-3]

At the Labour party conference, Gaitskell ruled out membership of EEC as the end of Britain as an independent state and a 1000 years of history – and the end of the Commonwealth.

By 1983, the Labour manifesto – the longest suicide note in history in the words of one of its MPs – pledged to take Britain out of the EEC. Michael Foot, the leader of the party, opposed membership in 1975 in terms that almost outdid Farage in 2016: ‘The British parliamentary system has been made farcical and unworkable by the superimposition of the EEC apparatus. It is as if we had set fire to the place as Hitler did with the Reichstag’.

4. Agriculture

Concern over CAP now shifted. It was locked into he EEC, and it was possible to find a reason to accept it.

In the 1975 referendum, the focus turned to food security with concerns about a Malthusian crisis by reports from the Club of Rome: CAP might mean higher prices but would prevent shortages. The era of cheap food was over.

Margaret Thatcher campaigned for remain and said that ‘most housewives would rather pay a little more than risk a bare cupboard. In the Common Market we can be sure of having something in the larder’. [Saunders 278.]

An agony aunt made the point in a politically incorrect manner : ‘Like the day of the red-coated soldier beating the living hell out of fuzzy-wuzzies, the day of cheap food has now gone’. [Saunders 278]

The remainers shifted the ground from cheapness to availability. Callaghan predicted that EEC prices would converge to world prices – ‘The prospect is therefore that membership of the Community, a major food-producing area, will offer us greater stability of prices at reasonable levels, and security of supply in times of shortage’. [Saunders 290]

The leavers were easily portrayed as irrational and extreme: a combination of Enoch Powell, the IRA, CPGB, Soviets. On the other side, remainers seemed rational: the Conservative and Liberal parties, the National Farmers Union, Australia and NZ.

The referendum of 1975 was a victory for remain – so why did attitudes then shift by 2016?

WHAT HAPPENED TO UNDERMINE SUPPORT?

A selective list could point to six factors

- Britain was chained to a corpse

The European Union was no longer seen as a wake-up call:

- advance of neoliberalism in the UK and decline of social democracy: EU came to seem statist and controlling. Rejected by free-market fundamentalists who see Britain as buccaneering. Leaving would complete the Thatcherite agenda – she had warned at Bruges of risk of defeating socialism at home only for it be reintroduced from Brussels.

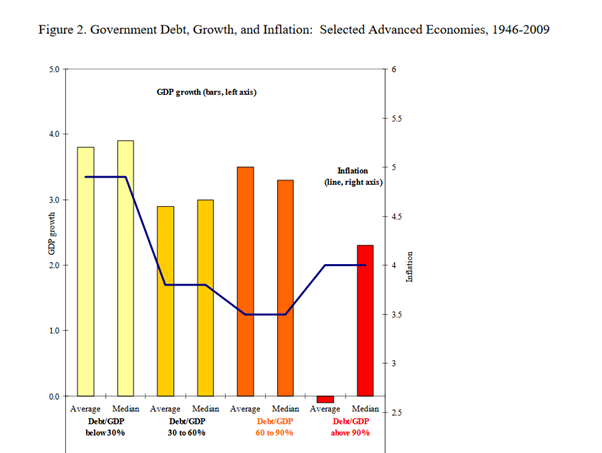

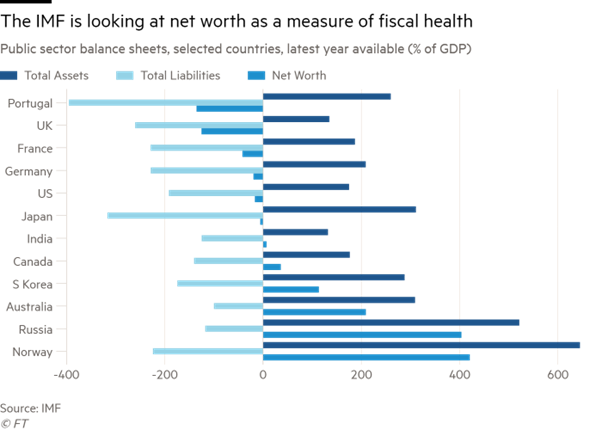

- European growth was slow

- Institutions of labour market were rigid and inflexible (in eyes of right) – and European rules ran against desire for labour market flexibility.

- Eurozone crisis and lost decade: although Britain was not in the eurozone, it no longer seemed the European economy was the future compared with BRICS. An upward trend in negative attitudes to EU started in 2010 with eurozone crisis [Clarke, Goodwin, Whiteley 72] This could appeal to the left as well as right – to Corbyn, who sympathised with Benn from 1970s, it proved his point: the exploitation of Greece for the benefit of German industrialists.

- Eurozone and migrant crisis made EU look incompetent – unfortunate timing of the referendum in 2016.

- 2. Deindustrialisation and globalisation

We can understand why attitudes shifted in declining industrial areas – by 2016 there was not a single Durham miner, or for that matter scarcely a Sunderland shipbuilder. In 1975, workers in these sectors still had good wages and status – miners, shipyard workers had skills which were specific to a trade and not based on formal qualifications. They relied on tangible capital.

Since 1975, these areas deindustrialised – not as a result of the EEC but of changes in technology. Even if industry produced the same amount of goods as before, fewer workers were needed. The issue was not globalisation or the European single market. [Tomlinson]

In 2016, the older skills were worthless and were competing with similarly low-skilled workers from EU – benefits went to those with formal qualifications, able to handle abstractions and intangible capital.

Supporters of EU failed to grasp the anger of those who were suffering. A Bank of England report argued that a 10 per cent increase in the proportion of migrants was associated with a 2 per cent reduction in pay for unskilled workers in services such as care homes, shops, bars [Clarke, Goodwin, Whiteley 12] – and this outcome was given emotional force by images of refugees crossing the Med or arriving in Germany. Areas of low pay, high unemployment, a tradition of manufacturing and lower skilled workers voted to leave [Becker, Fetzer, Novy]

By contrast, the better educated benefited from lower trade barriers and were not affected by the free movement of labour – they likely to benefit from valuable skills that were attractive in job markets in EU and world. [Clarke, Goodwin, Whiteley, 62-3] Hence 37 per cent of university graduates voted leave compared with 60 per cent without a university education; 35 per cent of upper and upper middle class voted leave compared with 64 per cent in working/lower classes.

Hyper-globalisation and the ‘elephant curve’ of Branco Milanovic contributed to the outcoe. He showed

Two sets of winners: middle class in emerging markets and global plutocracy

Losers the working/lower middle class in developed world

The well-off elite argued that immigration was a net benefit, that it was misleading to complain for they brought valuable, hard-working people who were younger people who paid taxes; they were not a drain on wealth of idle white working class. The real problem was not migration or transfers to the EU that led to queues for medical care, pressure on schools or housing – rather it was austerity.

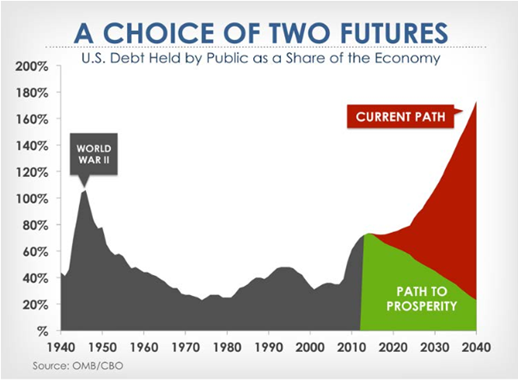

3. Austerity

The real issue was not the migrants who were net contributors to taxation but were widely seen as leading to problems in NHS, schools, housing. Those problems did exist, and wages were stagnant. It was claimed – falsely – that leaving EU would give £350n a week to NHS – the issue was not Brussels but austerity after 2010.

Austerity was an entirely self-inflicted wound – led by David Cameron and George Osborne with the complicity of the LibDems who were campaigning to remain. Austerity had nothing to do with Brussels – other than indirectly in seeing what it did to Greece.

In France, incomes of lowest 50 per cent of the population rose by 32 per cent since 1982 – unlike in Britain. The Piketty graph shows that inequality within Britain [U shaped, returning to the level around 1900], compared with France [L shaped. So no returning to previous levels].

Communities were left to cope with the consequences of globalisation with less help from central government. The Brexit vote was related to austerity and poor provision of public services – and found to be more significant than immigration in determining the vote. Vulnerable populations were becoming more dependent on the state which stopped mitigating the rise of inequality with radical austerity in 2010, activating grievances and converting them into hostility to EU. It is possible that that a modest reduction in austerity would have reversed the decision. [Becker et al; Fetzer]. Corbyn did not articulate this – he hated austerity but did not like the EU either.

The flaw of Cameron and Osborne was that they wanted efficient markets, but did not do what was needed to retain popular support for them. The result was to hurt the market – or ironically to hand over influence to those who argue for Brexit as a cover for even more market fundamentalism.

4. Has Britain ever got over winning the war?

Europe moved on from the Second World War – Britain did not. We can note the ways that the war and its legacy are commemorated:

In France, commemoration is part of Europe: Macron referred to France not standing alone in First World War, needing Canadians, British, Italians US. The political message is pro-European – the French Prime Minister at Compiegne in 2017 remarked that ‘to love peace is to love Europe’.

In Britain, there is little mention of others in the armistice service, except Commonwealth. Instead, there is a myth of standing alone. A memo written for Cameron concerning the commemoration of First World War said that ‘we must ensure that our commemoration [of the First World War] does not give any support to the myth that European integration was the result of the two World Wars’ [O’Rourke p6]. Commemoration was led by a Brexiteer MP, Andrew Murrison. The Irish economic historian Kevin O’Rourke remarked: ‘If words fail you then I’m afraid I can’t help, for they fail me too’.

It was argued by some in 1975 that joining the EEC was a betrayal of those who fought against Nazis. Hence Enoch Powell saw Britain in ‘a life and death struggle with other weapons and in other ways, the contention is as surely about the future of Britain’s nationhood as were the combats which raged in the skies over southern England in the autumn of 1940’. [Saunders 53] But such views did not have traction – especially in the context of the Cold War.

Such views became more important in 2016 when they were linked to a sense of superiority and deep grievance that British sacrifices were not give their due; it was a revolt against imagined oppression. O’Toole [8] refers to a pleasurable self-pity of being hard done by, of winning the war and losing the victory, with a precipitous fall from being the heart of empire to an occupied colony or vassal state. It is what O’Toole [102] calls the ‘metapolitics of exaggerated grievance’

The shift is apparent in the words of Roger Helmer in 2018 [a former Cons and now UKIP MEP]: ‘When I was born, I was not European citizen (and my father’s generation fought to ensure we should not be German citizens). I am determined that I shall not die as a European citizen’. He Implied that Europe was German project – and this was often made explicit (and had some traction in progressive circles given the harsh treatment of Greece by Germany and a suspicion that the euro kept exchange rates more competitive than would have been possible with the Deutsch Mark). In 1989 Kenneth Minogue of LSE argued that ‘the European institutions were attempting to create a European Union in the tradition of the medieval popes, Charlemagne, Napoleon, the Kaiser and Adolf Hitler’. Boris Johnson in May 2016 similarly commented that the EU was an attempt to do by different methods what Napoleon and Hitler tried – the EU was ‘pursuing a similar goal to Hitler in trying to create a powerful superstate’.

The European Union was now seen as a surreptitious take over and defeat, a plot – it was sold EEC as a common market not a European super state. This rhetoric took bizarre forms such as the mad cow war when German alarm about eating CJD beef was turned by the hyperventilating Daily Mail into a showdown ‘on a scale scarcely seen since the Battle of Britain’.

This reading of history was summed up by

Mark Francois in Jan 2019 when the German CEO of Airbus warned of the consequences

of Brexit for manufacturing wings in North Wales: ‘Mr Enders’

intervention is a classic example of the sort of Teutonic arrogance, which is

one of the reasons why many people voted to leave the European Union…. My

father Reginald Francois was a D-Day veteran, he never submitted to bullying by

any German, neither will his son.’ He

then ripped up the letter live on BBC.

It seems that many people had watched too many films like Our Finest Hour

and Dunkirk, and endless repeats of Dad’s

Army. Ironically, the remain campaign in 1975 recruited Captain Mainwaring

(the actor Arthur Lowe) to its cause. [Saunders 108].

Jacob Rees-Mogg reached heights of absurdity in Oct 2017: ‘We need to be reiterating the benefits of Brexit…. Oh, this is so important in the history of our country… It’s Waterloo, it’s Crecy! It’s Agincourt! We win all these things’. He neglected to point out that the Prussians played a major role at Waterloo, and that the victories at Crecy and Agincourt were interludes before the loss of French territory.

5. Identity

Concerns about national identity were more important than economics: a fear of loss of cultural identity.

In the 1966 World Cup, the flag used by English supporters was the Union jack – Englishness and Britishness were interchangeable. This ceased to be the case: the cross of St George replaced the union jack.

The Census of 2011 asked for self-identification: in England 60 per cent identified as solely English (77 per cent in the north-east, 37 per cent in London) compared with 29 per cent as English and British.

There was a clear shift with the movement for Scottish independence: in 1996 a survey found that only a third of the English chose to be identified as English rather than British; this rose in 2011 to half. Scots could seek freedom from London – England could not seek freedom from London but could from Brussels. [O’Toole 190]

Mike Kenny argued in 2014 that the re-emergence of English national identity ‘may well turn out to constitute one of the most important phases in the history of the national consciousness of the English since the 18th century’.

6. Revival of the anglosphere

This shift in identity has links with the return of the Anglosphere or CANZUK or empire 2.0 as it was sarcastically called by civil servants – a new union not with Europe but with the white empire. Britannia Unchained (2012) was a neoliberal project of deregulation, following the example of buccaneers who made the empire by pursuit of private wealth, released from the ties of EU. One of authors was Dominic Raab. It was in a tradition going back to 19th century – J R Seeley, imperial federation, Anglo-Saxondom of Cecil Rhodes, idea of English-speaking people (in which allow India).

Anglosphere became a right-wing movement as in conferences of Hudson Institute in 1999 and 200, including David Davis, the minister for exiting the EU, and members of the Heritage Foundation. Some of key participants wrote for the Murdoch and Conrad Black press; and there were links with the Charles Koch Foundation and Cato Institute. Pearce and Kenny [131] comment that ‘the fusion of Anglospheric thinking and neo-liberal ideas emerged as a vibrant ideological pattern’. They point out that the appeal is to a free market, neo-liberal future against the more statist approach of Brussels. The Anglosphere is useful as a way of imaging Britain as a global, deregulated privatised economy – it provides a mask for otherwise unpalatable ideas which do not appeal in areas suffering from austerity and decline.

Nigel Farage urged in April 2014: ‘Let’s re-embrace the big world, the 21st century global world. Let’s strike trade deals with India, New Zealand, all of those emerging parts of the world’. The UKIP manifesto in 2010 claimed that ‘Britain is not merely a European country, but part of a global community, the Anglosphere…. From India to the United States, New Zealand to the Caribbean, UKIP would want to foster closer ties with the Anglosphere’. [Pearce and Kenny 145] . David Davis took a similar line in 2016: ‘This is an opportunity to renew our strong relationships with Commonwealth and Anglosphere countries. These parts of the world are growing faster than Europe. We share history, culture and language. We have family ties. We even share similar legal systems. The usual barriers to trade are largely absent’. [Pearce and Kenny 153]

CONCLUSION

The outcome of the referendum in 2016 had deeper roots than any use of social media or misleading claims about immigration or funding for the NHS. Britain had good rational reasons for stay aloof after the war, and when governments did turn to membership, it was for instrumental and contingent reasons that soon evaporated. In 2016, the remainers had greater problems in finding reasons to support the EU than in 1975 when it seemed to offer a route to prosperity and faster growth; in 2016, the eurozone crisis made the EU took weak and risky. The Brexiteers had an easier option of offering change and disruption, a promise of freedom and sovereignty and growth. Any attempt to suggest there were risks could be rejected as ‘project fear’ and had the weakness of being negative. But many of the possible arguments were over-looked. The argument in 1975 about sovereignty was used by the leavers with the notion of ‘take back control’ – though the EU was acting against American tech giants that were a greater threat to sovereignty; the loss of revenue from base erosion and profit shifting by multinational corporations exceeded payments to the EU; and there was little understanding of what leaving on WTO rules meant. The decision was made – now it remains to be seen at what costs.

References:

SO Becker, T Fetzer and D Novy, ‘Who voted for Brexit? A comprehensive district level analysis’, Economic Policy 32 (2017)

Harold D Clarke, Matthew Goodwin and Paul Whitley, Brexit: Why Britain Voted to Leave the European Union Cambridge University Press, 2017

T Ftezer, ‘Did austerity cause Brexit?’ Warwick Economics Research Papers 1170 2018

Benjamin Grob-Fitzgerald, Continental Drift: Britain and Europe from the End of Empire to the Rise of Euroscepticism Cambridge University Press, 2016

Mike Kenny, The Politics of English Nationhood Oxford University Press, 2016

Mike Kenny and Nick Pearce, Shadows of Empire: The Anglosphere in British Politics Polity, 2018

Alan S Milward, The United Kingdom and the European Community, I: The Rise and Fall of a National Strategy 1945-1963 Cass, 2002

Kevin O’Rourke, A Short History of Brexit: From Brentry to Backstop Pelican Books, 2018

Fintan O’Toole, Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain Head of Zeus, 2018

Robert Saunders, Yes To Europe! The 1975 Referendum and Seventies Britain Cambridge University Press, 2018