National debt and austerity

/in Blog/by Martin DauntonIn April 2009, G20 leaders from the world’s major developed and emerging economies met in London under the chairmanship of the British Prime Minister, Gordon Brown. It was a critical time as demonstrators took to the streets of the City of London, and the world faced the prospect of the financial crisis turning into something akin to the Great Depression of the 1930s. Indeed, Brown explicitly made a link with the World Monetary and Economic Conference held in London in 1933 that failed with disastrous consequences for the global economy and ultimately for peace.[1] He warned that the stakes were high and cooperation was needed to avoid a repeat of the downward spiral into trade and currency wars of the 1930s. History was called on to provide guidance – but the participants at the London summit in April 2009 had very different readings of history.

A return to Keynesianism?

One approach was to return to John Maynard Keynes whose response to the Great Depression was to reject ‘balanced budgets’ and to argue for budget deficits to rebalance the economy. By Keynes’s account, the depression was caused by a lack of demand which led to excess capacity so that savings were not invested. The solution was to boost demand through public works and a budget deficit, which would then create an outlet for savings and lead to economic recovery. The G20 summits of 2008 and 2009 seemed to make ‘the return of the master’, to take the title of a short book by Keynes’s biographer, Robert Skidelsky.[2] The summit of November 2008 marked, in the opinion of the Financial Times, a ‘sudden resurgence of Keynesian policy’ with a commitment to ‘use fiscal measures to stimulate domestic demand to rapid effect’, within a policy framework ‘conducive to fiscal sustainability’. The G20 communique in April 2009 confirmed this return to Keynes: ‘we are undertaking an unprecedented and concerted fiscal expansion, which will save or create millions of jobs… that will, by the end of next year, amount to $5 trillion, raise output by 4 per cent, and accelerate the transition to a green economy. We are committed to deliver the scale of sustained fiscal effort necessary to restore growth’.[3] In 2008, the United States adopted the Economic Stimulus Act which offered tax rebates to stimulate consumption, and in 2009 the American Recovery and Investment Act to boost public spending. But the revival of Keynesianism and public spending were short lived.[4]

The fiscal stimulus was modest and soon gave way to fiscal consolidation or ‘expansionary austerity’ – a belief that the way to growth was through cuts in public spending designed to restore balanced budgets. Austerity was portrayed on the right as natural and self-evident: the state was inefficient and drove out private investment; public debt was a curse and could not be sustained. Debt sustainability became the priority rather than employment or growth, and governments embarked on programmes to cut the budget deficit and national debt.[5] Criticism came above all from Germany. Peer Steinbruck, the Social Democrat finance minister in Angela Merkel’s coalition government, criticised Brown’s ‘crass Keynesianism’ for ‘tossing around billions’ that would place a burden of debt on future generations.[6] Jurgen Stark of the European Central Bank and formerly vice-president of the Bundesbank saw a ‘substantial risk’ of a repeat of the 1970s: ‘I really cannot see why discretionary fiscal policies, which have proven to be ineffective in the past, should work this time’.[7] The concerns were not confined to Germany, the home of fiscal rectitude. Even in Britain, Mervyn King, the Governor of the Bank of England, intervened in political debates by expressing his concern about further increases in the size of the deficit by fiscal stimulus and argued that ‘monetary policy should bear the brunt of dealing with the ups and downs of the economy’.[8]

In February 2010, the major economies in G7 embraced austerity, and at Toronto in June 2010 the G20 announced a commitment to ‘growth-friendly fiscal consolidation’ or more bluntly, austerity.[9] Even the Keynesians had to admit that there had been a structural deficit when the economy was booming and that steps were needed to control spending. It was therefore hard to justify large-scale public spending even at a time when interest rates were low. Instead, fiscal rules were introduced, including by left of centre governments. These rules ran from a moderate ‘golden rule’ that the return on any new debt was to be higher than the cost of servicing the loan, or a more rigid rule that the budget must balance over the cycle or even annually.[10] In the eurozone crisis, austerity to reduce budget deficits and the national debt were imposed on southern European countries and Ireland, with a refusal to reschedule the debt or default, unlike in earlier episodes both before the First World War and in the Mexican crisis of 1982.[11] The message that debt was bad, that the crisis had been caused by improvident behaviour by the state, was easy to explain to voters.

My aim in this paper is to explain why Keynesianism and fiscal stimulus were defeated by austerity and Quantitative Easing. My first point is that the shift was justified by a lesson from history – that the Great Depression was a result of inappropriate monetary policy by the Federal Reserve which must now be avoided.

The triumph of monetary policy: a ‘lesson’ from the Great Depression

In his memoir of the crisis, Ben Bernanke, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, drew a stark contrast between the actions of the Federal Reserve in the 1930s and after 2007:

In all crises, there are those who act and those who fear to act. The Federal Reserve … failed its first major test in the 1930s. Its leaders and the leaders of other central banks around the world remained passive in the face of ruinous deflation and financial collapse. The result was the global Great Depression, breadlines, and 25 per cent unemployment in the United States, and the rise of fascist dictatorships abroad. Seventy-five years later, the Federal Reserve … confronted similar challenges in the crisis of 2007-2009 and its aftermath. This time, we acted.[12]

Bernanke was a self-confessed ‘Great Depression buff’ and he was obsessed with the question of why the Great Depression occurred and why it was so deep and long. He generalised from the Great Depression to argue that problems in the financial system lead to serious economic downturns. In a recession, banks become more cautious in their lending and borrowers are less credit-worthy. As a result, credit is less available, and both household purchases and business investments decline, so intensifying the recession. Falling or stagnant prices and wages mean that borrowers are less able to keep up existing loan repayments than at times of rising prices and wages when the real level of debt falls. Consequently, borrowers cut discretionary spending to keep up payments and are less able to borrow for new purchases.[13]

He followed in the steps of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwarz’s reinterpretation of the Great Depression as a monetary phenomenon. They argued that the contraction of the money supply just before the crash of 1929, and again in the early years of the Great Depression, led to a sharp drop in prices, falling wages, and postponement of purchases in the expectation of lower prices in the future. In their view, the Fed could have taken ‘different and feasible actions’ to prevent the decline in the stock of money, so reducing the severity and length of the Great Depression. Instead, the monetary policy of the Fed was inept.[14] On the occasion of Friedman’s 90th birthday in 2002, Bernanke made a public statement of apology on the behalf of the Fed: ‘I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again’.[15] He had, as the title of his memoir would later put it, ‘the courage to act’, and the Fed responded to the Great Recession as it did in part as a result of the lessons he drew from history.

The lesson drawn from the Great Depression was to pursue monetary policy rather than fiscal stimulus, and on 18 March 2009, the Fed embarked on Quantitative Easing. But arguably it was the wrong – or at least, not the only – lesson from history. Two leading economic historians, Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’Rourke used the historical record of the Great Depression to argue that, in the few cases where it had been tried in the 1930s, fiscal policy and deficit finance worked, and that governments after the Great Recession should take advantage of low interest rates to borrow, increasing public spending until households, banks and firms could take up the slack.[16] Their historical analysis went largely unheeded and instead politicians turned to another interpretation of the past to argue that high levels of debt were harmful to growth – the so-called ’90 per cent rule’ proposed by two leading economists with close ties to the IMF and Federal Reserve – Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart.

The ‘ninety per cent rule’

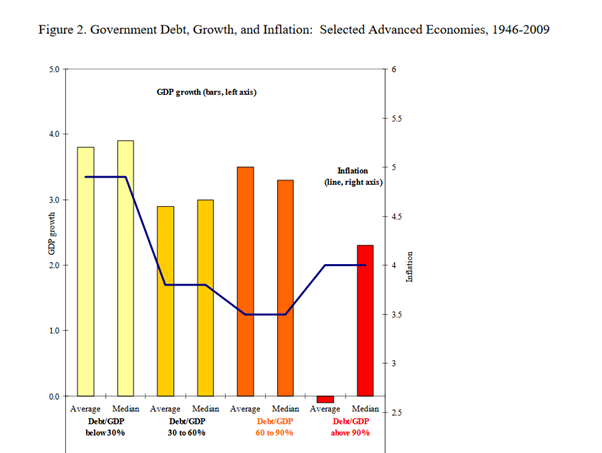

In January 2010, Reinhart and Rogoff’s issued a working paper ‘Growth in a time of debt’ for the National Bureau of Economic Research, based on a dataset of 44 countries over 200 years, with over 3,700 annual observations covering a wide range of political systems, institutions, exchange rate mechanisms and historical conditions. They argued that a debt to GDP ratio above 90 per cent led to a fall in the median growth rate by 1 per cent, and even more in the average rate and in emerging markets (see figure 1). They found that ‘seldom do countries simply “grow” their way out of deep debt burdens’. They argued that ‘debt intolerance’ appeared when debt rose, with an increase in the risk premium and a consequent need to ‘tighten fiscal policy in order to appear credible to investors and thereby reduce risk premia’. The political consequence of this finding were serious. Although the Maastricht criteria for membership of the euro specified that a country’s deficit should be no more than 3 per cent of GDP and the debt/GDP ratio no more than 60 per cent, many members were exceeding these limits – and the conclusion of Reinhart and Rogoff was that the level of debt was reducing growth and therefore making escape more difficult. For their part, the United States had a debt to GDP ratio of 103 per cent and Japan of 230 per cent in 2014. If Reinhart and Rogoff were to be believed, reducing the debt was vital for economic recovery.[17]

FIGURE 1

Source: ‘Growth in a Time of Debt’, Carmen M. Reinhart, Kenneth S. Rogoff, NBER Working Paper No. 15639, Issued in January 2010, Revised in December 2011

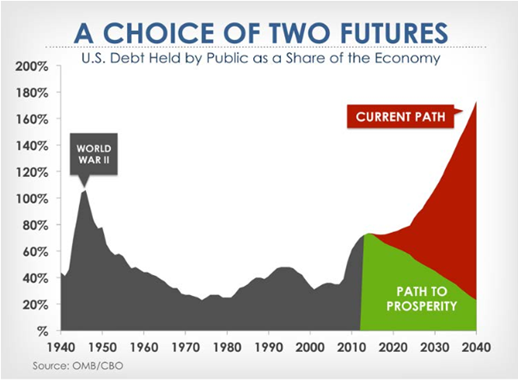

The calculations of Reinhart and Rogoff were soon challenged as inaccurate, with a correction of their data suggesting that the average country with a debt over 90 per cent of GDP grew by 2.2 per cent rather than declining by 0.1 per cent. Nevertheless, they claimed that the relationship remained and their views were widely disseminated in the press.[18] Politicians on the right seized on a seductively simple ’90 per cent rule’ that if the debt were not stopped, it would rise inexorably until the country collapsed in bankruptcy. Paul Ryan, the Republican chairman of the House Committee on the Budget, cited their study to argue that debt above 90 per cent ‘has a significant negative effect on economic growth’. He drew a stark choice between two futures: a path to prosperity, with debt completely paid by the 2050s; or a path to economic disaster as debt rose to almost 900 per cent of GDP by 2080. In his view, the obvious sources of this ‘crushing burden of debt’ was social security, Medicare and Medicaid.[19] (see figure 2) In February 2010, shortly before he became Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, George Osborne commented that the study of Reinhart and Rogoff was ‘perhaps the most significant contribution to our understanding of the origins of the crisis’. It offered him some intellectual justification for his ideological belief in a smaller state.[20] Reinhart and Rogoff themselves were more nuanced, proposing that debt could be reduced not only by austerity but also by restructuring both sovereign debt and mortgages on houses, or by reducing real interest rates which amounted to a tax on bondholders.[21] What was simply not politically feasible was an increase in American taxation to European levels to cover social spending and stop the debt from rising.[22]

FIGURE 2

Source: The Path to Prosperity: A Responsible, Balanced Budget. The House Republican Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Resolution

More seriously than the errors in the spread sheets, the ninety per cent rule is bad history that was used for ideological purposes. Context matters and the observations of Reinhart ad Rogoff did not distinguish between different circumstances. Above all, there is no mention of war. A major reason for peaks in debt was warfare which complicates the relationship with economic growth. The ratio of debt to GDP exceeded or was close to 200 per cent in Britain during the Napoleonic and both world wars (see figure 3). High debt in the Napoleonic wars was associated with the industrial revolution, and over the ‘long eighteenth century’ from 1688 to 1815, Britain sustained a much higher level of debt and taxation without default than did France. Simply put, there was a contrast between the French revolution and the industrial revolution. The national debt in Britain was sustained by an effective fiscal system and bond market in the City of London that contributed to the growth of an efficient financial system that sustained commerce, unlike in France which experienced frequent default.[23] During the First World War, the level of debt in Britain again rose and the economy experienced a decade of low growth – not as a result of debt so much as the collapse of the global economy and overvaluation of sterling with the need for high interest rates to maintain parity . By contrast, a higher level of debt as a result of the Second World War coincided with, perhaps even stimulated, rapid economic growth as a result of fiscal stimulus and the recreation of a global economy.[24] The ability to pay down the debt after war depends on interest rates – high after 1918, low after 1945 – and growth rates – low after 1919 and higher after 1945.[25]

FIGURE 3

It might be argued, with considerable justice, that high levels of debt created by the pressures of warfare are different from the recent situation where debt has increased in peacetime and even at periods when the economy has been running at full capacity as the result of a structural deficit. This is a fair point, and nothing that is said here is intended to justify improvident spending and maintenance of a deficit. But warnings about over-spending should not become reasons for slashing spending without considering other factors. Action to reduce the deficit and debt might be justified where debt is serviced by high levels of taxation of productive wealth and income which harms growth; on other occasions, it is serviced by taxation of high earners that shifted income to poorer members of society and increased consumption. Similarly, a cut in public spending to balance the budget might possibly lead to growth if debt, interest rates and taxation were high (as in Italy in the 1980s and 1990s), but not necessarily in other circumstances. One of the real lessons of history is that context matters and ‘rules’ as laid down by Reinhart and Rogoff are misleading and even dangerous.[26] A crucial is why the deficit arises. Spending on education, technology and infrastructure might raise the rate of growth and produce a rate of return that is as high as or even higher than private sector investment. On the other hand, the deficit could arise – as it has in the United States – from extravagant spending on defence or military adventures. From expensive subsidies to the drug companies in Medicare, as well as generous tax cuts. The structural deficit may be reduced without cutting spending that benefits growth and employment. Stiglitz rightly argues that the argument above the deficit in the United States, and one might add in the United Kingdom, has been shaped by politicians and economists whose concern is less about the size of the deficit and how to reduce it than about the size of government and the level of progression in the tax system. It is, in his opinion, ‘a wolf’s agenda in sheep’s clothing’.[27]

Reinhart and Rogoff refer to ‘debt intolerance’ and the risk of a higher risk premium with the need to restore credibility by austerity. But their own work shows that credibility is not only a matter of the level of debt – it also reflects the existence of a credible tax regime. The comparison between Britain and France in the long eighteenth century shows that a country can sustain a higher level of debt and taxation where the state and fiscal extraction has a higher level of legitimacy. Similarly, in This Time Is Different, Reinhart and Rogoff show that Greece defaulted over half of the time since it secured independence and its tax system was inadequate. Indeed, it was not reformed after the bail-outs and rescheduling prior to the First World War. Debt crisis in the Ottoman Empire, Egypt and Greece before the First World War led to international financial control and an opportunity to reform the tax system. In Egypt and the Ottoman empire, more progress was made in the absence of democracy than in Greece, where democracy and the need for political negotiation within parties and parliament led to blockages.[28] This historical record suggests that the risk premium on Greek debt should be high; in fact, it fell with membership of the eurozone. Up to the financial crisis, the risk premium on sovereign debt of members of the eurozone fell to a very narrow range. In July 2007, the interest rate on 10-year Irish sovereign bonds was actually lower than on German debt, reflecting the complacent assumption that eurozone sovereign default was impossible. This situation soon proved untenable. Risk premiums rose and rates between countries became more dispersed. By January 2009, the risk premium on Irish sovereign debt had risen to 300 basis points, at which point the Irish government rescued the Anglo-Irish bank at a cost of around 20 per cent of Irish GDP. The crisis in banking spilled over into alarm at public debt and the risk premium rose to over 1,000 basis points.[29]

Of course, both Reinhart and Rogoff and the Maastricht criteria assume that the debt to GDP ratio is the most appropriate measure. But is it? Both are statistical constructs and should be treated with caution. Diane Coyle has set out the complex story of GDP measures, what they include and exclude. As she points out, there is now debate over how to capture complicated global production chains, how to measure ‘intangibles’ that are a larger share of the economy, and how to deal with sustainability, given that an increase in the GDP can come at the cost of destroying ‘natural’ capital and so passing costs to the future.[30] Similarly, public debt can be manipulated by drawing the line between the state and non-state actors, such as through the use of public private partnerships or Private Finance Initiatives that were adopted particularly by the ‘new Labour’ government in Britain: the capital cost of hospitals or schools is raised by the private sector, and does not appear as national debt, though the charge for the use of the asset might be more onerous. A recent analysis by Avner Offer points out that ‘Placing debt off the balance sheet was a deception which provided no benefits. It was a “fiscal illusion”, no more than an accounting trick. There was no saving, just the opposite. A much higher cost was imposed on future taxpayers in order to present the semblance of prudence and self-control.’ The construction of large-scale capital projects with long time horizons is ideally suited to state finance at low interest rates but PFI schemes allowed bankers to secure a revenue flow at money market rates with a guarantee underwritten by the credit of the state. Howard Davies, the former chairman of the Financial Services Authority, Audit Commission, and Royal Bank of Scotland was in a good position to castigate PFI in 2018 as ‘a fraud on the people because essentially the government is always the cheapest borrower’. [31] Focussing on reducing the ratio of debt to GDP might be a false economy for public spending and debt create assets which are handed to the next generation. If the state spends more on productive assets at a time of low interest rates, and those assets encourage economic growth, the result would be to reduce the debt to GDP ratio. Instead, the turn to Quantitative Easing led to an increase in the value of equities held by richer people and left the poor suffering from a reduction in welfare.

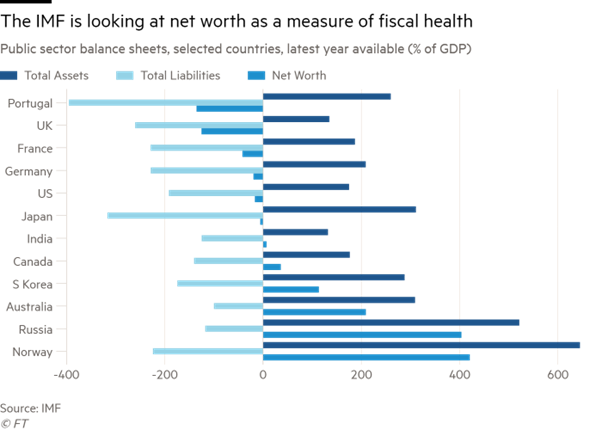

The measure of GDP to debt could be replaced by another measure: the ratio of debt to national assets to produce the net worth of the state (assets minus liabilities). Borrowing to invest is different from borrowing for consumption, and high-return public investments can raise growth, unlike spending on warfare or handouts to the financial and other corporate sectors.[32] In 1957, the net worth of the public sector was about 30 per cent below GDP but it rose to about 75 per cent in 1979. The ‘great divestiture’ of the Thatcher and Major governments marked a fundamental change, with net worth falling to under 20 per cent of GDP. Apart for the sale of council houses to their former tenants at a discounted price, the sale of public assets largely benefitted managers who secured higher salaries and financial interests, rather than customers – so contributing to a rise in inequality. It did not lead to popular, widespread share ownership; nor did it have a major impact on productivity. The sale of the assets contributed to debt repayment in the 1990s, offering a short-term wind-fall at the expense of future income. Indeed, the net worth of the UK is lower than any country except Portugal according to a recent IMF report – and Japan moves from being the heaviest debtor in terms of debt to GDP to somewhere in the middle of the table (see figure 4). In the words of Viktor Gaspar of the IMF, ‘it is not only what you owe; it’s what you own’. The IMF pointed out that countries with stronger balance sheets pay less interest on their debt and that well-run state enterprises could add up to 3 per cent of GDP to the revenue of the state.[33]

FIGURE 4

The point was well made by AB Atkinson that the focus should not be on reducing the ratio of debt to GDP:

We should be focussing on the overall net worth of the state, not just on the national debt. The proper objective of fiscal policy should be a return to a situation where the state has a significant positive net worth. Of course, the reduction of the national debt would contribute to this end, but it is only one side of the equation. The other side is the accumulation of state assets. By holding capital and by sharing in the fruits of technological developments, the state can use the resulting revenue to promise a less unequal society.

The solution was not necessarily a return to nationalisation for there were other possibilities such as the creation of a sovereign wealth fund such as in Singapore or Norway, or some form of mixed ownership with management left in private hands. In his view, a state with a positive net worth can create a fairer society within and across generations than one in which individuals pass on their assets to their descendants, leading to growing inequality.[34]

Of course, Atkinson’s approach valued the state – a belief that ran counter to the attack on the state since the 1970s. This attack went through two stages. The first was a crisis of the tax state in the 1970s which meant that revenues were not large enough to cover demands for welfare at a time of the economic crisis – so leading to a turn to debt to make up the shortfall. By making higher taxes politically unacceptable, and in some cases such as the United States during the Reagan presidency making unsustainable tax cuts, the result was a greater reliance on debt. The second stage was then to attack reliance on debt as imprudent. Why, then, did the tax state suffered from a legitimation crisis in the 1970s?

The crisis of the tax state

High levels of debt are not necessarily the result of an unusually large public sector or high levels of social service expenditure. Elliot Brownlee and Eisaku Ide argue that debt in the United States and Japan reflects a relatively low tax effort with attempts to increase taxes in the 1980s facing opposition.[35] The point can be extended, for Wolfgang Streeck argues that hostility to tax increases led to a crisis of the tax state in the 1970s, leading to the creation of a ‘debt state’ to defuse distributional conflict between capital and labour. Monetary expansion inserted more resources to extend the promise of ‘socially pacified capitalism, but resulted in stagflation. The outcome was a growing reliance on debt to meet the needs of workers beyond the capacity of the economy. In Streeck’s view, the containment of taxation was a first stage of a neoliberal agenda; the next stage was the ‘consolidation state’ to reduce public spending, with a growing reliance on private debt to supplement income from work. The process is apparent in the United Kingdom where government debt in 1995 was about 58 per cent of GDP and household debt 72 per cent; by 2008 the figures were 61 per cent and 110 per cent. Streeck sees a new legitimation crisis of democratic capitalism, for the consolidation state on longer produces even the illusion of equitable growth. Streeck calls for a turn from market justice to social justice.[36]

It is not necessary to follow Streeck’s argument that there was an internal contradiction between capitalism and democracy to agree that there was a crisis of taxation and public finance in the 1970s.[37] The oil shock of 1973 led to a recession in most OECD countries. Cheap oil had served as one of the main motors of the impressive growth rates in Western countries. Now, increases in the price of petrol exacerbated the incipient economic crisis at a time when the benefits of a shift of labour from low productivity agriculture into manufacturing were largely exhausted, and the gains of post-war technological changes had been captured.[38] Most OECD countries slipped into recession. The rise in oil prices led to a dramatic increase in production costs for industry and also in the energy costs of private households, contributing to a fall in consumption outside the energy sector. In most Western countries the crisis consisted of high inflation rates, falling production, rising unemployment and balance of payments deficits. The result was the end of the boom. In Western Europe growth in GDP per capita was 4.05 per cent from 1950 to 1973, but only 1.75 per cent from 1973 to 1997.[39] Expectations for welfare had been raised but the economic system could not deliver.

By the 1970s, profits were being squeezed in many industrial economies, so that it was difficult to balance the claims of capital, wages and consumers and to maintain capital investment.[40] Investment in manufacturing was only 5.4 per cent of gross capital stock in 1960‒1968 in Britain, but much higher in Japan (9.4 per cent) and Germany (19.1 per cent). The oil price shock after 1973 and the rising costs of borrowing in the 1980s led to a fall in investment in manufacturing in most countries: in Britain it fell to 3.1 per cent of gross capital stock in 1980‒1988, and even more strikingly in Japan to 5.8 per cent and Germany to 10.2 per cent. In Germany and Japan, about two-thirds of the fall in investment can be explained by declining profitability; surprisingly, in Britain the effect of profits was modest.[41]

The squeeze on profits meant that the social contract between labour, capital and the state on which the boom rested started to break down. After the war, the social contract was based on workers trading lower current consumption for higher living standards in the future, based on the belief that industrialists would reinvest their profits. Commitment to the deal was underwritten by the government through tax-breaks on condition that firms invested, by schemes for industrial support, and by welfare benefits for the workers. Barry Eichengreen argues that this neo-corporatist ‘web of interlocking agreements’ increased the cost of bringing the post-war settlement to an end.[42] But by 1970 the contract was breaking down as profits fell, squeezed by the demands for higher wages which could no longer be covered by gains in productivity. One response was to turn to debt to meet expectations.

The end of the Bretton Woods system constituted another major challenge. On 15 August 1971, President Richard Nixon suspended the convertibility of the United States dollar into gold. The subsequent attempts to return to pegged exchange rates failed, leading to a new exchange rate system.[43] The Bretton Woods regime was based on a desire to stabilize exchange rates and at the same time allow individual countries to pursue an active domestic monetary policy. These two aims could be reconciled only by limiting the movement of capital in response to different interest rates, for free flows of capital would put pressure on the fixed exchange rate – the so-called trilemma which allowed a choice of only two of fixed exchange rates, capital movements, and an active domestic monetary policy. The Bretton Woods trade-off came under pressure with growing freedom of capital movement after currencies became convertible in 1958, and with the emergence of the Eurodollar market and the relaxing of capital controls in the 1970s. The greater scope for movement of capital between countries allowed more freedom in monetary policy but constrained independence in taxation policy, for if a country adopted policies that were too redistributive or costly for markets to tolerate, they would be punished by capital flight. The rise of the Eurodollar market also increased opportunities for evading taxation and contributed to the growth of tax havens.[44] The result was both to make more funds available for borrowing by governments and to make higher taxation more difficult given the risk of capital flight.

It was also difficult to rely on taxation given changing cultural assumptions about what was considered to be fair, just and equitable. A major shift in the 1970s was from collective to individualistic approaches to society. Dan Rodgers has termed this the ‘age of fracture’ in the United States, defined by a movement away from concepts of national consensus, managed markets and citizen responsibility to a more fluid sense of gender and racial identities, narrower definitions of collective responsibility, and the replacement of solidarity in terms of class or race by fluid, multiple identities. Keynesian macroeconomics was overtaken by flexible, instantly acting markets and by the individual interest of public choice theory. Rodgers argues that solidarity and collective institutions gave way to a more individualized sense of human nature based on choice, agency, performance and desire. ‘Strong metaphors of society were supplanted by weaker ones. Imagined collectivities shrank; notions of structure and power thinned out.’ Social assumptions shifted through a ‘contagion of metaphors’, as central features of game theory moved from economics departments into law and the social sciences, and out into the wider public discourse. The notion of ‘choice’ was employed more frequently and became an inherent claim on both the progressive left – for example, a woman’s right to abortion or an individual’s right to sexual identity‒ and the conservative right ‒ the freedom to choose how to spend one’s own money. Both used the rhetoric of choice, though for different ends.[45]

This shift in attitudes is connected to a change in the nature of political mobilization from the 1960s. The mass political parties that emerged in the nineteenth century were coalitions of different interests, making concessions to construct a general platform for which members would campaign, even if they were not entirely happy about all the elements. This pattern weakened from the 1960s with greater mobilization on single issues rather than a common platform. Issues such as feminism and sexual politics, or the politics of consumption, suffer from what Geoff Eley has called the ‘tyranny of structurelessness’ with decentralized and non-bureaucratic forms of mobilization. In his view, the ‘empowerment of participation’ of 1968 was difficult to convert into a response to the emergence of global capitalism.[46]

At the same time, politicians on the right sold a more optimistic future to a weary electorate, offering ‘populist market optimism’ that was expressed in the significant tax cuts of 1979 and 1981 in Britain and the United States. These ideas were popularized in two best-sellers published in the United States. The first was Jude Wanniski’s The Way the World Works which advocated a supply-side approach, arguing that a ‘wedge’ of taxation interrupted trade between producer and consumer; if it could be reduced, the economy would flourish. The Democrats offered spending to help the poor; rather than oppose spending, the Republicans should promise tax cuts which, they claimed, would restore full employment and so contain pressure for public spending and reduce the size of the public sector.[47] The second was George Gilder’s Wealth and Poverty, which presented an optimistic account of economic growth once entrepreneurs had been unshackled from the fetters of taxation; Reagan made sure that the members of his cabinet were given copies.[48]

Historians have grappled with the reasons for the change from collective to individual attitudes to taxation and the state. In broad terms, it is often said that it amounts to a rise of neoliberal ideas,[49] but why did they have purchase now? An economistic interpretation of the shift is provided by public choice theory through the self-interest of voters seeking to maximize their utility and deciding whether paying taxes for the collective provision of public services was beneficial. There are two ways of explaining a change in the perception of the costs and benefits of taxation. The first way is to look at the relationship between the franchise and taxation. Until 1970, most voters in Britain fell below the income tax threshold, and certainly below the higher rate threshold. Thus they were likely to benefit from public spending without making a proportionate contributing to it, and so had good reason to vote for more generous welfare and higher taxes. As wages rose and tax thresholds did not increase in line with inflation, more voters began to pay income tax or were liable at a higher rate – indeed, they could experience a very high marginal rate by losing benefits and coming into the purview of direct taxes. The politics of direct taxation had changed. After the war, the median voter earned a modest income, falling below the threshold for income tax. This gave rise to strong electoral support for direct taxation. By the 1970s, the median voter was paying income tax at a high rate and so eroded support for direct taxation.

A second way of looking at the changing assumptions of taxpayers and the electorate is to consider the relationship between the incidence of taxation and the receipt of benefits. In some countries, such as Britain, social benefits were funded by direct taxes largely funded by middle-class voters. Initially, the middle class might feel that they were getting a reasonable deal, for they might disproportionately benefit from greater access to healthcare and secondary and higher education; and at a time of high employment, there was less concern that benefits were being used to support the ‘undeserving’ poor. A public choice analysis suggests that the attitude of middle-class taxpayers would change by the 1970s. The somewhat generalized pattern of welfare provision after the war seemed attractive at the time, but rising incomes and advances in healthcare created a demand for more individualized and targeted provision. Greater disposable income and paying higher taxes for a basic level of provision seemed less attractive to a generation with different assumptions about consumer choice created in the decades of affluence in the 1950s and 1960s. Why not opt out of the state system and purchase what they wanted? By contrast, in some countries direct taxes were much less important and the costs tended to fall on consumption: thus whereas in the United Kingdom consumption taxes comprised 27.6 per cent of total taxation in 1970, they accounted for 50.5 per cent in Ireland, 38.3 per cent in Italy and 36.5 per cent in France.[50] This different tax structure modified the assumptions of the electorate, for the middle class was less inclined to pay high income tax rates to fund benefits for less well-off members of society who were now defined as ‘scroungers’, than in a system where costs fell on indirect taxes. Could it be that a less progressive tax regime mitigated the hostility of voters with incomes above the median to provide redistributive welfare benefits?

The economic crisis of the early 1970s meant, as Rodgers’ says, ‘a breakdown in economic predictability and performance’.[51] A similar point is made by Daniel Stedman Jones who sees the emergence of neoliberalism as the result of the economic crisis of the 1970s and the acceptance – on the left as much as the right – of the need for new policies to fill a policy vacuum in response to the collapse of the Bretton Woods system and the onset of stagflation. John Hicks – an economist closely associated with the triumph of Keynesianism ‒ pointed out in April 1973 that the General Theory was devised to deal with deflation and offered no solution to the problem of rising inflation, and especially the combination of high inflation and high unemployment which seemed impossible in classical Keynesianism. Consequently, there was a crisis of Keynesian economics.[52] Ideas for an alternative approach had been evolving in a network of think tanks and pressure groups. In Stedman Jones’s words, ‘just as in 1932 or 1945, the 1970s were a rare moment when the pieces of the political and economic jigsaw were strewn all over the place, in need of painstaking rearrangement’.[53]

The new democratic states of Southern Europe – Portugal, Spain and Greece – faced particular issues. Their welfare systems lagged behind the rest of Europe, and they opted for a fiscal regime of progressive income tax rather than the French or Italian approach of high consumption taxes to overcome widespread tax evasion. Their problem was that they lacked the capacity to administer such a system through a well-trained tax bureaucracy, so leading to tax fraud and evasion.[54] Consequently, they were left with the problem of how to finance their emerging welfare systems. They turned to the same solution as Italy – to overcome tax fraud by using the central banks that were dependent on the government in order to monetize large and recurrent budget deficits. They also relied on ‘financial repression’, delaying financial deregulation of domestic banks in order to oblige them to hold government debt and to hold down the interest payment. The result was to plug the gap between welfare demands and fiscal capacity by reliance on monetary expansion and debt.[55]

For these reasons, increases in tax revenue were negligible in comparison with the boom period. With expenditures continuing to grow, governments increasingly relied on borrowing to meet their financial obligations, helped by the oil money in the Western banking system. The level of government debt in the wealthy OECD countries steadily rose. The debt state had arrived – and when the financial crisis arrived, any move to increase taxes to fund welfare was rejected. Instead, the deficit and debt had to be reduced.

Bait and switch: rhetorical strategies

I have so far argued that the defeat of Keynesianism and fiscal expansion can be explained by the triumph of monetary policy as a result of a particular reading of the history of the Great Depression, by the use of the 90 per cent rule to justify retrenchment, and by the rejection of higher taxation. A further reason is the notion of ‘bait and switch’ – that is, explaining that there is a problem with the deficit and debt levels, and then switching the explanation from the costs of bailing out the banks to the public’s demand for generous welfare benefits.[56] The result was noted by Stiglitz: ‘deficit fetishism’ was used as a way of justifying reduction in the size of the government and the progressivity of the tax system, and of avoiding alternative approaches that would hit vested interests of the military-industrial complex or large corporations. In his view, ‘the financial sector has imposed huge externalities on the rest of society. America’s financial industry polluted the world with toxic mortgages, and, in line with the well established “polluter pays” principle, taxes should be imposed on it.’ A plausible view of the debt crisis is that the high cost of bailing out banks led to a fiscal burden and to deflation in an attempt to close budget deficits. Worries about sovereign debt led to a loss of confidence in banks which held government bonds; the costs of rescuing banks hit public finances; and austerity weakened economies and made it harder to deal with the deficit. The result was a vicious downward spiral. But the narrative that took precedence was that a bloated and inefficient state and generous welfare provisions fuelled the deficit and the rise of the debt.[57]

Economists and commentators on the left rejected Ryan’s explanation of the rising ratio of debt to GDP, and instead argued that the financial crisis of 2008 led to higher debt as a result of bailing out the banks. In their view, debt was cyclical and could be reduced by faster growth stimulated by fiscal policies. In the words of Mark Blyth, a leading critic of austerity,

we have turned the politics of debt into a morality play, one that has shifted the blame from the banks to the state. Austerity is the penance – the virtuous pain after the immoral party – except it is not going to be a diet of pain that we shall all share. Few of us were invited to the party but we are all being asked to pay the bill.

On this view, high levels of public debt arose from the bail out of the banks, but those who were culpable passed the blame to the state, with the costs falling on the poor. The rhetoric of austerity provided a moral justification by shifting blame to a bloated and inefficient public sector and overly generous welfare.[58] This strategy rested on the economic ideology of the Virginia school of economics associated with James Buchanan, that the state was a rapacious Leviathan that needed to be contained. Cutting taxes and allowed debt to rise was a way of ‘starving the beast’ by imposing tax cuts and provoking a fiscal crisis in order to create support for cuts in spending and welfare as the only viable solution. Indeed, it was the Democratic administration of Bill Clinton that produced a surplus of $86.4 billion in 2000; the deficit returned under George W Bush, reaching $568 billion in 2004. The Republicans feared that a surplus would encourage more spending which could only be stopped by tax cuts and a budget crisis that could chain the state.[59]

At the heart of the rhetoric was a supposed identity between personal prudence and public finance, and the need to ensure that burdens were not passed to future generations. This take me to a further reason for the defeat of fiscal policy

The analogy of the individual and the state

Every individual is mortal and expects to pay off a loan at some point. Creditors are willing to lend several times the annual income in young adulthood, mainly for house purchase, but the amount will decline over life. By analogy, the state should not continue to accumulate debt which is passed on to future generations – a common justification for debt repayment and austerity. But is this a sensible argument? States do not die and older citizens are replaced so that communal debt does not need to be paid off in the same way. It is therefore possible to continue with a steady-state debt. Further, where the debt is held by citizens of the country – as it the case for two-thirds of British and even more of Japanese debt – it is not a net liability of that country’s citizens.

The question to ask is whether the debt is sustainable. Debt has risen since the recession as the state has taken on private bank debt and growth rates have fallen as a result of the recession and austerity. It is true that a large debt causes distortions because it needs taxation to service it and reducing the debt now would reduce taxation in the longer run. But in the short run reducing the level of debt means either higher taxes that might increase disincentives and reduce output or, more likely, cuts in welfare that hit the poor. The question is whether the long-term benefits are worth more than the short-term pain. Debt reduction replaces a steady time–profile of taxation and benefits by imposing higher taxes (or lower welfare) now for lower taxes (or better welfare) later. It is entirely possible that the distortions in the short run are greater than the reduction in distortions in the long run, and the sacrifice is not worthwhile. And the welfare costs of debt reduction are not linear: an IMF paper estimated that paying down 5 per cent of GDP leads to a 1 per cent welfare cost, rising to 6 per cent where 20 per cent is paid down.[60]

Indeed, the short-term pain has long-term consequences. The imposition of austerity in southern Europe has led to very high levels of unemployment for young adults which will affect their life chances in the long term. And it is not only the young who suffer, for there is also a fall in life expectancy. In Greece, health spending fell from 9.8 per cent of GDP in 2008 to 8.1 per cent in 2014, and GDP itself fell. The death rate rose by 17.6 per cent between 2010-16.[61] Bond holders and banks were protected at the expense of long-term unemployment and premature death. In 2015, an IMF report concluded that it might indeed be better to pay interest now rather than reduce the debt by austerity, and to wait for growth and inflation to have their effect:

For those countries that are not at imminent risk of losing market access, current policy debates center on the appropriate pace at which to pay down public debt. Those who believe that debt is bad for growth favor a rapid reduction in indebtedness, whereas those who stress Keynesian demand management considerations argue for a measured pace of consolidation, perhaps with a ramping up of public investment while interest rates remain at historic lows. Somewhat lost in this debate is the possibility of simply living with (relatively) high debt, and allowing debt ratios to decline organically through output growth….. [T]his third course, of living with high debt, merits consideration in countries where debt sustainability concerns are not pressing.

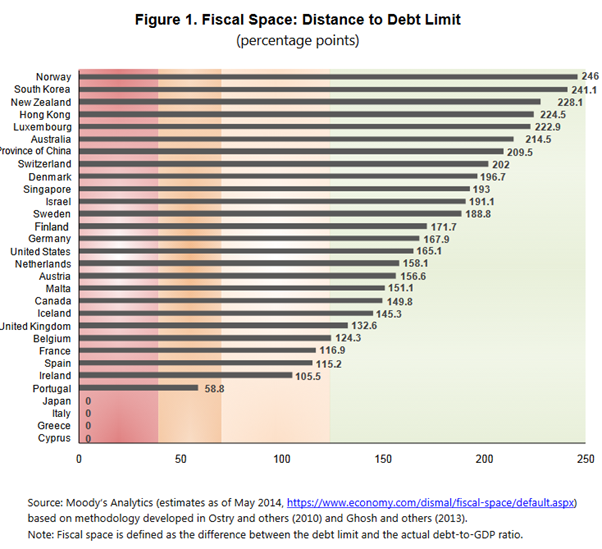

Whether it is possible to live with high debt depends in large part on the ‘fiscal space’ between the actual debt to GDP ratio and debt limit that might trigger a crisis (see figure 5). This is not an invitation for Greece to carry on regardless – it is for a partial default or restructuring to avoid the pain of austerity, and then to ensure that a credible tax regime is created. There was no compelling reason for countries to embark on austerity when they had sufficient fiscal space.[62]

FIGURE 5

From Ostry, Ghosh and Espinoza, ‘When should public debt be reduced?’

Conclusion: the problem of the future

A recent report of the UK Office of Budget Responsibility in January 2017 predicted that the austerity programme would bring the debt ratio down from 90 per cent to 80 per cent by the end of the 2020s. The welfare costs started to have serious political consequences for the government of Teresa May who announced in September 2018 that austerity would end. But the OBR report calculated that the public sector deficit and debt would grow to 234 per cent by 2066/7 – a level higher than during the three periods of warfare. The explanation is in part an erosion of the tax base with globalisation and tax avoidance, and pessimism on future growth prospects, even leaving aside the impact of Brexit. Above all, the reason is an ageing population with the consequent costs of health, social care and state pensions, and the obligations to pay pubic sector occupational pensions. The government’s assets more than cover government borrowing (a slightly different measure from national debt) but not the occupational pension entitlements and financial liabilities from quantitative easing. (see table 1)

TABLE 1 AROUND HERE

Whole of government accounts for UK, 2015/16, £ billion

Liabilities

Government borrowing £1,260.6

Public-sector occupational pension entitlements £1,424.7

Not funded – paid out of current taxation

Financial liabilities (arising from QE) £557.4

Other £485.7

Total £3728.4

Assets £1,742.4

Net liabilities £1,986.0

Source: Martin

Slater, The National Debt: A Short History London, 2018, 244

Here is a serious issue, for the costs of ageing and of the pension obligations are paid by younger workers who will not themselves have similar benefits. The growth of inequality both between classes at a point in time, and between generations over time has been worsened by austerity and debt reduction. What can be done? One solution is to leave individuals to provide their own welfare through the free market, continuing the reduction in taxes and debt. Another is to boost economic growth to accelerate out of debt, though this depends on policies to ensure that growth is inclusive. The more radical solution is to turn back the erosion of the tax state of the 1970s. Atkinson and Piketty propose measures such as a wealth tax, property tax, and progressive lifetime capital receipt tax which now seem utopian.[63]

What I suggest is that the shift from fiscal policies and public spending after 2009 for a policy of Quantitative Easing and austerity created more problems than it solved, leading to widening disparities of income and wealth. Instead of action to resolve the impact of hyper-globalisation and technical change on social disparities, the policies of QE and austerity led to Brexit and the election of Trump which were linked with market fundamentalism. The question is whether the situation can now change. The problem of an ageing population and increased costs of care and pensions needs to be tackled – and the solution is likely to require an increase in taxation and a reconsideration of the politics of public finance. The 1970s marked a crisis of the tax state; will the 2020s mark a crisis of the consolidation state with the possible return to a more equitable society? It will only happen if ‘bait and switch’ and the rhetoric of austerity can be countered. In the United States in 2018, the prospects are not hopeful. Large tax cuts for the rich and corporations are leading to renewed deficits, and Republicans such as Paul Ryan have abandoned their earlier apocalyptic visions of mounting debt now that it arises from tax cuts to the rich rather than benefits for the poor. When the crisis does arrive, the danger is that the response will be cuts in spending that could stimulate growth rather than the restoration of tax cuts. But other solutions are possible, and the virtue of historical analysis is to show that what now appears the natural order of things has not always been so.

notes

[1] Interview in Daily Telegraph, 30 Jan 2009. He returned to the comparison on several occasion: see Simon Robinson and Catherine Meyer, ‘Gordon Brown: sometimes a crisis forces change’, Time 25 March 2009.

[2] Robert Skidelsky, Keynes: The Return of the Master London: Allen Lane, 2009

[3] Chris Giles, Ralph Atkins and Krishna Guha, ‘The undeniable shift to Keynes’, Financial Times 30 Dec 2008; London summit – leaders; statement, 2 April 2009; Barry Eichengreen, The Hall of Mirrors: The Great Depression, the Great Recession, and the Uses and Misuses of History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014, 10, 340-2.

[4] The stimulus was less than suggested at the G20: see Chris Giles, ‘Large numbers hide big divisions’, Financial Times, 3 April 2009.

[5] Eichengreen, Hall of Mirrors, 7, 9-10, 282, 284, 332-3; Austerity measures are outlined in BBC website, ‘EU austerity drive country by country’, 21 May 2012; Alberto Alesina and Silvia Ardagna, ‘Large changes in fiscal policy: taxes versus spending’, NBER working paper 15438, Oct 2009.

[6] Philip Stephens, ‘Summit success reflects a different global landscape’, Financial Times, 2 April 2009

[7] Giles, Atkins and Guha, ‘Undeniable shift’.

[8] Chris Giles, ‘UK bank chief urges caution’, Financial Times, 25 March 2009; evidence to House of Commons Treasury Committees: Bank of England February 2009 Inflation Report, Oral and Written Evidence, Tuesday 24 March 2009, Q97 at www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200809/cmselect/cmtresy/376-i/376i.pdf

[9] The G20 Toronto Summit Declaration, 26-27 June 2010, http://www.g20.utoronto.ca/2010/to-communique.html

[10] The rules are set out in Eleva Bora, Tidiane Kinda, Priscilla Muthoora and Frederick Toscani, ‘Fiscal rules at a glance’, IMF April 2015 at http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/FiscalRules/Fiscal%20Rules%20at%20a%20Glance%20-%20Background%20Paper.pdf. See also X. Debrun, L. Moulin, A. Turrini, J. Ayuso-i-Casals and M. S. Kumar, ‘Tied to the Mast? National Fiscal Rules in the European Union’, Economic Policy, April 2008, and Charles Wyplosz, ‘Fiscal rules: theoretical issues and historical experiences’, in Alberto Alesina and Francesco Giavazzi (eds.), Fiscal Policy After the Financial crisis Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013, at http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12656.pdf

[11] R P Esteves and A C Tuncer, ‘Eurobonds past and present: a comparative review on debt mutualization in Europe’, Review of Law and Economics 12 (2016) and ‘Feeling the blues: moral hazard and debt dilution in Eurobonds before 1914’, Journal of International Money and Finance 65 (2016).

[12] Ben S Bernanke, The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and its Aftermath New York and London: WW Norton, 2015, vii

[13] Bernanke, Courage to Act, 30, 33-35

[14] Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960 Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963, pp. 301, 407-419. See the correction to their view in Eichengreen, Hall of Mirrors, 114-6.

[15] Bernanke, Courage to Act, 65.

[16] Eichengreen, Hall of Mirrors, pp.6-7, 284, 301; Miguel Almuni, Agustin Benetrix, Barry Eichengreen, Kevin O’Rourke and Gisela Rua, ‘The effectiveness of fiscal and monetary stimulus in depressions’, at http://www.voxeu.org/article/effectiveness-fiscal-and-monetary-stimulus-depressions.

[17] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, ‘Growth in a time of debt’, NBER Working Paper 15639, Jan 2010; see also Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of Fiscal Folly Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

[18] Their statistics were challenged by Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin, ‘’Does high debt consistently stifle economic growth? A critique of Reinhart and Rogoff’, Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts Amherst, WP series no 322, April 1013, at www.peri.umass.edu/fileadmin/pdf/working_papers/working_papers_301-350/WP322.pdf

[19] The Path to Prosperity: Restoring America’s Promise. Fiscal Year 2012 Budget Resolution, House Committee on the Budget, Chairman Paul Ryan Wisconsin.

[20] George Osborne, ‘Mais Lecture: A new economic model’, 24 Feb 2010

[21] Reinhart and Rogoff, ‘Debt, growth and the austerity debate’, New York Times, 25 April 2013; ‘Why we should expect low growth amid debt’, Financial Times 28 Jan 2010; J Cassidy, ‘The Reinhart-Rogoff controversy: a summing up’, New Yorker 26 April 2013.

[22] Martin Wolf, ‘The radical right and the US state’, Financial Times, 12 April 2011; the case for cutting spending rather than increasing taxes was made by Alesina and Arganda, ‘Large changes in fiscal policy: taxes versus spending’, see Blyth, Austerity, pp. 173-6 and Iyanatul Islam and Anis Chowdhury, ‘Revisiting the evidence on expansionary fiscal austerity’ at http://voxeu.org/debates/commentaries/revisiting-evidence-expansionary-fiscal-austerity-alesina-s-hour

[23] P Mathias and P O’Brien, ‘Taxation in Britain and France, 1715-1810: a comparison of the social and economic incidence of taxes collected for the central governments’, Journal of European Economic History 5 (1976); J Brewer, The Sinews of Power: War, Money and the English State, 1688-1783 London: Unwin Hyman, 1989; PGM Dickson, The Financial Revolution in England: A Study in the Development of Pubic Credit, 1688-1756, London: Macmillan, 1967.

[24] Martin Daunton, Just Taxes: The Politics of Taxation in Britain, 1914-1979 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[25] Nick Crafts, ‘Reducing High Public Debt Ratios: Lessons from UK Experience’, Fiscal Studies, epub., 23 December 2015.

[26] See my own work on debt after the Napoleonic, First and Second World Wars in Trusting Leviathan and Just Taxes; Eichengreen, Hall of Mirrors, 10.

[27] For example, Joseph E Stiglitz, ‘Stimulating the economy in an era of debt and deficit’, The Economists’ Voice, March 2012 at http://www.degruyter.com/view/j/ev

[28] Reinhart and Rogoff, This Time Is Different; C Tuncer, Sovereign Debt and International Financial Control: The Middle East and the Balkans, 1870-1914, Houndsmill: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

[29] Paul Wallace, The Euro Experiment Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016, 82-3, 89; Ashoka Mody and Damiano Sandri, ‘The Eurozone crisis: how banks and sovereigns came to be joined at the hip’, Economic Policy 27 (2012), 201-6, 225-7; M Ehrmann, M Fratzscher, RS Gurkaynak and ET Swanson, ‘Convergence and anchoring of the yield curves in the euro area’, Review of Economics and Statistics 93 (2011).

[30] Diane Coyle, GDP: A Brief But Affectionate History revised edition, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014, ch. 6.

[31] Avner Offer, ‘Patient and impatient capital: time horizons as market boundaries’, University of Oxford Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History no. 165, August 2018, 11-19.

[32] Stiglitz, ‘Stimulating the economy’ and ‘Dangers of deficit-cut fetishism’, The Guardian 7 March 2010 at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/mar/07/deficit-fetishism-government-spending

[33] Chris Giles, ‘Cash strapped countries advised to manage assets better’, Financial Times 10 Oct 2018; World Economic and Financial Surveys. Fiscal Monitor October 2018. Managing Public Wealth IMF, Washington, 2018.

[34] Massimo Florio, The Great Divestiture: Evaluating the Welfare Impact of the British Privatizations, 1979-1997 Cambridge Mass and London: MIT Press, 2004; Anthony B Atkinson, Inequality: What Can Be Done? Cambridge Mass and London: Harvard University Press, 2015

[35] W Elliot Brownlee and Eisaku Ide, ‘’Fiscal policy in Japan and the United States since 1973: economic crises, taxation and weak tax consent’, in Marc Buggeln, Martin Daunton and Alexander Nützenadel eds., The Political Economy of Public Finance since the 1970s, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

[36] Wolfgang Streeck, Buying Time: The Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism London: Verso, 2014.

[37] Explored in Marc Buggeln, Martin Daunton and Alexander Nützenadel, ‘The political economy of public finance since the 1970s: Questioning the Leviathan’, in Buggeln, Daunton and Nützenadel eds., The Political Economy of Public Finance, 6-16.

[38] Karen R. Merrill, The Oil Crisis of 1973‒1974, Boston, Mass: Bedford Books, 2007; Mahmoud A. El-Gamal and Amy Myers Jaffe, Oil, Dollars, Debt and Crises. The Global Curse of Black Gold Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010{Die politischen und gesellschaftlichen Auswirkungen der arabischen Erdölpolitik auf die Bundesrepublik und Westeuropa, Stuttgart 1996.|.}

[39] Angus Maddison, Economic Progress: {The Last Half Century in Historical Perspective, 1999, Table 3a.|The Last Half Century in Historical Perspective, 1999, Table 3a, in www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/ARTICLES/madpaper.pdf. See also Niall Ferguson, ‘Introduction: Crisis, What Crisis? The 1970s and the Shock of the Global’, in ibid.; see also Charles Maier, Erez Manela and Daniel J. Sargent (eds.), The Shock of the Global. The 1970s in Perspective, Cambridge, Mass and London: Harvard University Press, 2010, 9. }

[40] Andrew Glyn and Bob Sutcliffe, British Capitalism, Workers and the Profits Squeeze Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1972, 66‒8;OECD, Towards Full Employment and Price Stability Paris: OECD, 1977.

[41] V. Bhaskar and Andrew Glyn, ‘Investment and Profitability: The Evidence from the Advanced Capitalist Countries’, in Gerald Epstein and Herbert Gintis, eds., Macroeconomic Policy after the Conservative Era Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, 190‒1.

[42] See Eichengreen, The European Economy, 31‒47; and ‘Institutions and Economic Growth: Europe after World War 2’, in Nicholas Crafts and Gianni Toniolo, eds., Economic Growth in Europe since 1945 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996, 38‒72.

[43] Francis J. Gavin, Gold, Dollars, and Power. The Politics of International Monetary Relations, 1958‒1971 Chapel Hill, NC: University Press of North Carolina, 2004.

[44] Harold James, International Monetary Cooperation since Bretton Woods New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996; Barry Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital. A History of the International Monetary System Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996; Gabriel Zucman, The Hidden Wealth of Nations. The Scourge of Tax Havens Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015; Ronen Palan, The Offshore World. Sovereign Markets, Virtual Places, and Nomad Millionaires Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003.

[45] Daniel T Rodgers, Age of Fracture Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass. and London, 2011, 3‒12. See also Pierre Rosanvallon, The Society of Equals Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 2013, ch. 4; Edward D. Berkowitz, Something Happened. A Political and Cultural Overview of the Seventies New York: Columbia University Press, 2005; Bruce J. Schulman, The Seventies. The Great Shift in American Culture, Society, and Politics New York: The Free Press, 2001.

[46] Geoff Eley, Forging Democracy: The History of the Left in Europe, 1850‒2000 Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, 378, 468.

[47] Jude Wanninski, The Way the World Works: How Economies Fail – and Succeed New York: Basic Books, 1978.

[48] George Gilder, Wealth and Poverty New York: Basic Books, 1981; Rodger, Age of Fracture, 69, 72.

[49] Angus Burgin, The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 2012 emphasizes Milton Friedman as a great persuader. See also Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe, The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 2009.

[50] Eurostat (ed.), Structures of the Taxation Systems in the European Union 1970‒1997 Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2000, 148.

[51] Rodger, Age of Fracture, 256.

[52] John R. Hicks, The Crisis in Keynesian Economics Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974. See also Maier, ‘Malaise’, 32‒8.

[53] Daniel Stedman Jones, Masters of the Universe: Hayek, Friedman and the Birth of Neoliberal Politics Princeton, NJ and London: Princeton University Press, 2012, 215‒16.

[54] Sara Torregrosa Hetland, ‘Did democracy bring redistribution? Insights from the Spanish tax system, 1960‒90’, European Review of Economic History (2015), 1‒22; and ‘Bypassing progressive taxation: fraud and base erosion in the Spanish income tax (1970‒2001)’, IEB Working Paper 2015/31 Chiara Bronchi and José C. Gomes-Santos, ‘Reforming the tax system in Portugal’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, 302 (2001).

[55] See Stefano Batalossi, ‘Structural fiscal imbalances, financial repression and sovereign debt sustainability in southern Europe, 1970s-1990s’, in Buggeln, Daunton and Nützenadel, Political Economy of Public Finance, 262-298.

[56] Mark Blyth, Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea New York: Oxford University Press, 2013, 5, 7, 73, 87

[57] Stiglitz, ‘Stimulating the economy’ and ‘Dangers of deficit-cut fetishism’; Blyth, Austerity, 5.

[58] Blyth, Austerity, 13-16.

[59] Adam Tooze, Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World London: Allen Lane, 2018, 27.

[60] Martin Slater, The National Debt: A Short History London: Hurst, 2018, 228-234; JD Ostry, AR Ghosh and R Espinoza, ‘When should public debt be reduced?’ IMF Staff Discussion Note June 2015 SDN15/10.

[61] ‘The burden of disease in Greece, health loss, risk factors and health financing 200-2016: an analysis of the Global Burden of Diseases Study, 2016’, The Lancet Public Health 3 (2018).

[62] Ostry, Ghosh and Espinoza, ‘When should public debt be reduced?’

[63] Atkinson, Inequality, 302-4; Piketty, Capital, Part 4.

Contact Information

Please use the for on the Contact page to send me an email.

Blog Archives

- December 2020 (1)

- July 2020 (3)

- October 2019 (1)

- September 2019 (3)

- July 2019 (2)